It was easy to write about the pedagogy of identity and its necessity in purely theoretical terms with examples from the praxis of master educators. In my own practice, it's a different story. In the Pedagogy for Restoration, I demand action of others but my book is most significantly a description of the demands I hold for myself. For that reason, I want to be entirely candid on this blog about my own struggle to learn to do this work. I hope that whether you read the book or not, we can use this as a space to learn and grow together. So please comment!

Over the past couple years, I have learned a lot about American cultures and started sharing some of those things with young people. I often think that it's not for me to teach, but I happen to be in the position to influence youth and I can see that many are starving to learn about their ancestors and cultures. I do put a lot of thought into how I approach such lessons, but I also occasionally see those unsure glances between my students during some of my lessons. I can tell they're sometimes uncomfortable and wondering if there is something wrong with what is happening - I wonder, too.

My impression so far is that despite the fact that I am certainly entering murky waters, the students want to be exploring their cultural identities and they want not to be made invisible. Still, having your identity acknowledged in a harmful way isn't any better than having it ignored - probably worse. I hope I'm not causing harm, but my choices are to quit trying because of the risk of doing it poorly or keep working at it. Unfortunately, I see too many people doing this work thoughtlessly or avoiding it altogether so I find that the fact that I care so deeply about this work is reason enough to keep trying.

I'm trying to help students explore their own identity, respect other cultures, and learn counterexamples to the 'whitestream' (a term I learned from Sandy Grande's fantastic book, Red Pedagogy) that dominate environmental and social restoration work; for example, the relationship (and distinction) between humans and nature. I don't see those goals as separate and while I don't believe students necessarily have an obligation to hold the beliefs of their ancestors, I do believe it is vital that we understand where we come from both as one people and as many peoples.

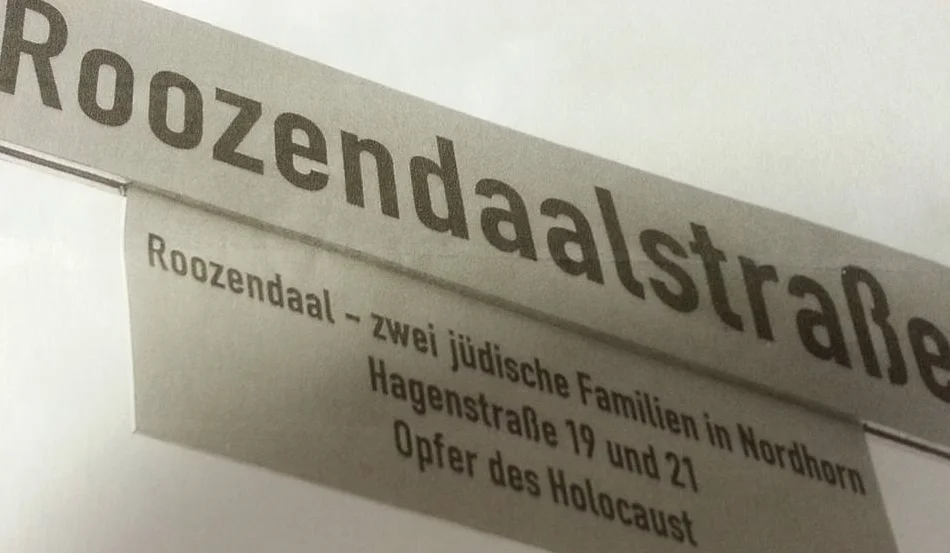

Not only am I committed to guiding students along this path, I am actively engaged with developing my own understanding of self and of what it is to be human. Furthermore, identity work is important to me because I know almost nothing about the history of my people other than the oppression we escaped. I don't identify very strongly as Jewish-American, and I mostly claim my Jewish identity in the memory of my grandparents and as a reminder for my commitment to justice. I want young people to learn about their people and to be proud of it because it's been a personal struggle for me. However you can't simply tell a student that they should be proud to be Mexican, or Native, or any other identity you might perceive them to be; that seems incredibly paternalistic and disempowering (especially coming from a white male). I think we have to take a multicultural approach with careful intention that none of the students feel as if their cultural identity is ignored, but our efforts must center on the identities most frequently and profoundly marginalized and ignored.

I've tried taking the perspective of my students to imagine how I might feel if someone who was not Jewish took it upon themself to help me figure out what it means to be Jewish. Almost certainly, no matter how carefully and respectfully they approached it, I would resent them for it; at least at times. I think I might also feel uncomfortable or outed among my peers. However, I wouldn't resent the knowledge I would gain and the fact is that I've never had a Jewish mentor to help me explore that aspect of my identity. My culture and history are things I do want to know about but for a lot of complicated reasons I have neither learned much myself or from my family.

Taking that perspective helps me to see that it's going to take a lot of work on my part and on the part of my students. We're both going to make mistakes and feel unsure along the way, but I think it's important enough that it's worth the risk. Although, I'm not entirely sure I'm getting there in my current position, this is a big part of the work that I am committed to doing. I believe it's one of the major components of a recipe for healing people and planet.

Still, I have this feeling sometimes that no matter how much I love culture there is a limit to how much I can truly understand and incorporate (is that a better word than appropriate?) into my own worldview when I've read it in books rather than lived it. At the same time, I feel like I've found more of myself through a multicultural search than I could have by explicitly tying to understand myself through an exploration of white Jewish-American culture, knowledge, and experience.

Despite the fact that I come at this with so much love, I'm not sure where the line between learning, respecting, honoring, and loving knowledge that does not belong to me and coming to believe that it does belong to me. I'm constantly worried about becoming one of those appropriative creeps who comes across as being entitled to pilfer the knowledge and traditions of all peoples.